Anti-Asian hate is not a symptom of the COVID pandemic, it has always existed.

Growing up Asian in a majority white town in the north of England meant that my experiences with hate started early. I was about eight years old when I had my first racist encounter. After school, I used to walk down a short path to meet my mum. A boy in the year above would follow me every chance he’d get, muttering under his breath, just loud enough for me to hear, “urgh, dirty Chinese, go back to China”, over and over. This was just the beginning.

For the rest of my formative years, and even now whenever I return home as an adult, my life would be punctuated by countless instances of anti-Asian racism. Sometimes it’d show itself in the form of ignorance – a teacher commenting how good my English is after having taught me for two years. Other times it would be cruel – classmates pulling their eyes and shouting “ching chong”. And then there were times when it was downright scary – grown men heckling my teenage self in the street when out on my first solo shopping trip with friends.

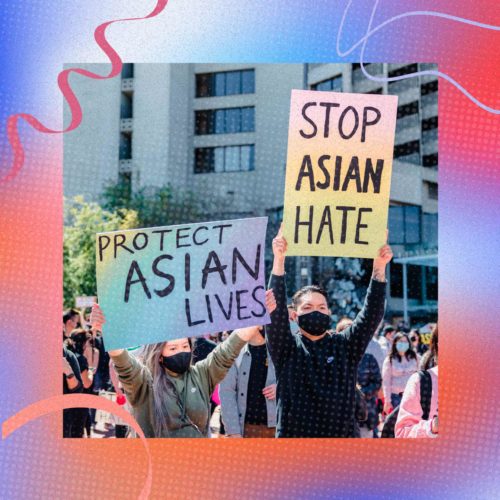

For the majority of our non-Asian readers, your awareness of anti-Asian hate is probably a recent development – a trending issue thrust into the public domaine at the expense of our elderly who were beaten in the streets, or the devastating, racially-motivated Atlanta shootings this past March. But though COVID, and the discriminatory rhetoric that followed, has undoubtedly exacerbated the issue, for most international Asians like me, the hate has been a part of our lives for as long as we can remember. The only difference now is that we’re finally talking about it.

Looking back at my experiences with anti-Asian hate, my immediate response has always been to try and ignore it. I’d tell myself that racism is just something that happens, there’s nothing you can do about it; next time, make more of an effort not to draw attention to yourself. But, after hearing the chorus of Asian voices in recent months, I feel compelled to stand in support.

So, as we reach what is hopefully the end of the pandemic – as life slowly starts to return to “normal” – I bring you a series of personal stories about growing up with anti-Asian hate, as told to me by friends abroad and in Hong Kong, many of which echo my own experiences as detailed above. Let them serve as a reminder that your support, solidarity and calls for justice are still very much needed, even when COVID is no longer a threat.

For my fellow Asian community, I hope you find comfort and resonance in the familiarity of these stories, in knowing you aren’t alone in your anger, fear and pain. For our wider audience, I hope they inspire empathy, and a fierce drive to make the world a more tolerant and accepting place.

Sassy Tip: Keep scrolling to the bottom for ways you can help stand against anti-Asian hate.

Read more: We Chat To The Founders Of HomeGrown Podcast About The Black Expat Experience In Hong Kong

Ginny’s Story

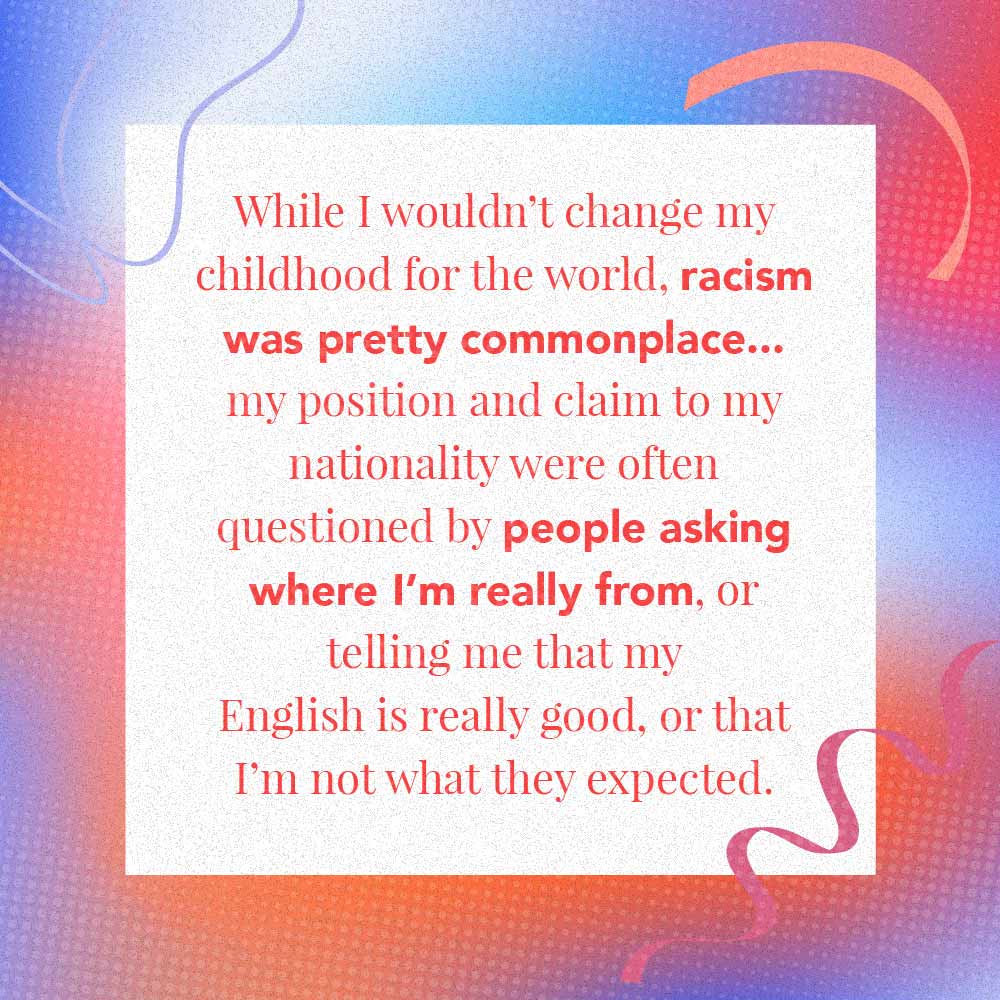

I grew up in a small, northern English town that was probably more than 90% white and predominately working class. My family was one of only a few Chinese families, and we all ran takeaways. While I wouldn’t change my childhood for the world, racism was pretty commonplace. My parents’ takeaway was in a fairly rough neighbourhood, and I’ve lost count of the number of times that children – my peers – had egged our windows, or broken the windows or glass door. We did also once have a firework thrown into the customer waiting area as well, though thankfully nobody was there at the time.

I was the only Asian person in my secondary school, and for the most part, my fellow students were fine. In Year 7, I had a boy follow me out from school and shout that my parents sold “fried monkey’s arse and chips”. I chose to ignore it, but my friends got him suspended from school. I’m forever grateful that they refused to let him get away with it.

Micro-aggressions were commonplace – my position and claim to my nationality (English, born and bred) were often questioned by people asking where I’m really from, or telling me that my English is really good, or that I’m not what they expected. Outright aggression has not been something I have generally encountered, other than angry shouting or the standard “ching chong chang China” hollered at me from across the road. One woman and her partner did, about seven years ago, very angrily verbally attack me for being a “chink” who had come over to “their” country to steal their jobs, but instances like that were very rare.

Read more: What I’ve Learnt Being British-Chinese In Hong Kong

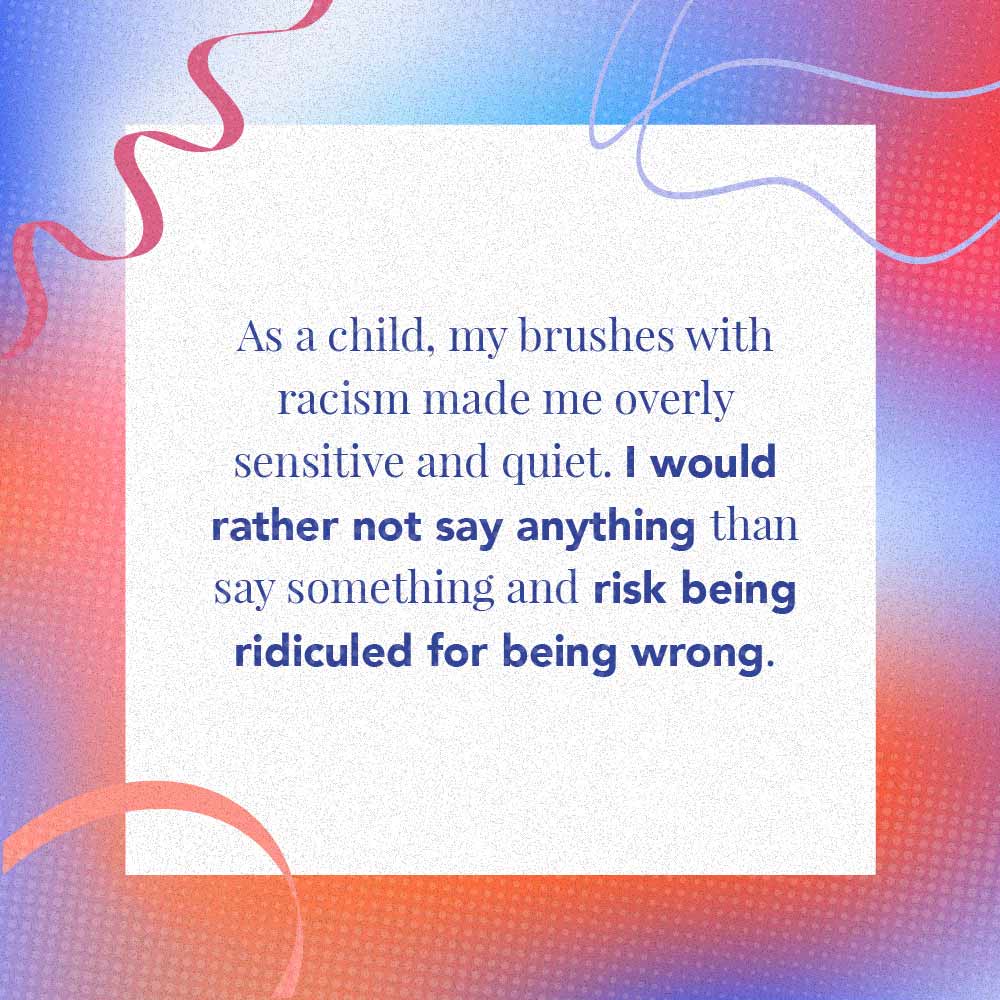

As a child, my brushes with racism made me overly sensitive and quiet. I would rather not say anything than say something and risk being ridiculed for being wrong. Whether I wanted to or not, these failures were invariably linked with feeling like I needed to be perfect because people would already have judged me or marked me down for being Asian. I felt like I needed to do more to achieve the same as my white counterparts. Was it real? Probably not, but it guided a lot of my actions as a child.

I’m not surprised to see the recent spike in hate crimes. We saw the same thing happen post 9/11 against Muslims and anyone who looked Middle Eastern, and if anyone is surprised by the same thing happening then they are being naïve. But just because I’m not surprised doesn’t mean I’m not incredibly angry, sad and distressed. It’s an issue that’s been exacerbated by Trump and social media echo chambers, and it feels especially harder to bear following the mass BLM protests.

I believe that there is a chance for change, I just don’t see it happening for a while. History tells us that people, on the whole, are quick to anger, but we’re probably slow to forgive or forget.

The spike in anti-Asian racism might not go away any time soon, but we’re also speaking up in ways we have never done before. As much as social media has created hateful echo chambers, it’s also been a fount of support and a real community for Asians across the world; it’s helping people to learn about the history of racism against Asians, it’s teaching people why the model minority model exists, and it’s encouraging people to stand up for themselves in thoughtful, impactful ways. Knowledge is how we affect change, and, thankfully, that is happening.

Jess W’s Story

Growing up as an Asian minority in the UK, I always wanted to be white. I remember being teased at school for having small eyes or bringing in Asian food for lunch. I hated speaking Chinese in front of my friends. For me, it was the “small” day to day instances when people shouted “ching chong” at you that made me feel angry and ashamed of my skin colour. I would attribute my physical insecurities as a teenager to my being Asian, never thinking I was as pretty as my white friends. I did a lot of music and remember being told that Asians have breathy voices so we don’t sing as well, or that we have small hands for the piano, and accepting it.

In a job interview once, at the end of an hour-long conversation, the interviewer told me he felt comfortable with my candidacy and would like me to progress to the next stage. And then he added “oh and your English seems ok too”. As a native English speaker, you can imagine my shock and horror. Patronising behavior like this would NOT be aimed at a white person – even if their English was worse than mine.

Ultimately, racism is deep-rooted in our society. The only difference now is that there’s been an increase in reported hate crimes against Asians post-pandemic, fueled by social media and the ease of information spread. But anti-Asian racism has existed since minorities began living among white communities.

With regards to the pandemic, I have been lucky enough to live among Asians since COVID, yet I’ve had discussions with expats who still like to use the term “Wuhan flu”, on the grounds that the virus originated in Wuhan. While I accept the logic, I do not think it’s acceptable to say this in the current anti-Asian racist environment. So please everyone, stop calling it that. You may not think you’re a racist, but you’re also indirectly propagating racism.

Maybe this is a sad thing, but I didn’t feel very surprised or emotional after seeing the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes. There’s a part of me that’s almost more surprised it hasn’t happened earlier. The main feeling was anger – at the public for not realising that anti-Asian racism has been around forever, at the media for not attributing the attack as race-related quick enough, and at world leaders for having legitimised racism in recent years.

I am pessimistic about the future with regards to anti-Asian hate, but I’m also a believer in the power of ideas to drive change from the bottom up. That means changes in education systems and in the media. Schools need to teach children how to be “global citizens” and what the meaning of respect looks like. People talk about diversity in workplaces – we need this, but we especially need diversity among teaching staff at schools.

The media also has a big responsibility – to write, show, illustrate and portray all corners of society, and in their most diverse forms. Only with changing ideas, attitudes and belief systems from the ground up can we enforce changes elsewhere like at large corporations or political systems. Otherwise, the claptrap we hear from brands, companies and politicians about D&I “initiatives” etc. is all a meaningless PR exercise.

Adrian’s Story

Growing up in England and attending an English school, I had experienced racism throughout with “casual” jokes regarding “eating dog”, “accent impressions” and having “small eyes”. I am quite thick-skinned so I have learned to live with it and not let it affect me. Additionally, I have experienced racism in public on the street with “ching-chang” comments.

As the COVID pandemic has gone on, I have experienced a number of clear incidents of anti-Asian racism in the UK. The first time, I was walking back from dinner with two other Asian friends along Oxford Street – a couple of youths cycling by shouted “Ew corona, stay away from me, don’t give it to me”. Another time, I was walking back from the shops and someone rolled their window down in the car and started shouting anti-mask conspiracy theories at me.

Jess H’s Story

Pre-pandemic, the types of racist comments I would typically receive were the “ni hao” and the “konichiwa” comments from strangers on the street. Sometimes it would be difficult to tell if these comments were related to being a woman on the streets of London as well. There were several times where my neighbours would ask me if I knew the Japanese couple who lived several streets away (for reference, I am Chinese), which could have been a mistake, or a type of subconscious bias.

These experiences with anti-Asian hate have affected my awareness and confidence. Simply walking down the street, I am conscious about who is looking at me, just in case it will lead to any abuse or violence.

With the increased anti-Asian hate we’ve seen in the past year, it has placed a level of distrust towards the world for me. I’m extremely disappointed in both the people who are committing the crimes, and those who are bystanders during the attacks.

Christine’s Story

I’m a third-generation Chinese-born Belgian. Growing up in a relatively small town in Belgium, I have always been quite insecure about my race, to the point where I was even ashamed of being Chinese. I just wanted to fit in with all my Caucasian friends.

I remember one incident at school during Dutch spelling class, the teacher was giving us examples of “-ng” sounds and she wrote “ching chang chong” on the blackboard and said, “Even Chinese people follow this spelling rule…” and then glanced over with a smile. I felt completely embarrassed and just laughed it off, which makes me so angry now, because laughing it off kind of justified the action and made it ok. I was infuriated and ashamed, but I didn’t want to cause a scene. I don’t necessarily think that she was a racist person, nor did she mean any harm by it, but I think that was a prime example of how easily anti-Asian racist jokes or slurs get thrown around, and how socially-acceptable it is to do so. Words can easily turn into actual crimes. The fact that after 25 + years, this is the only thing I remember from my spelling class proves that it had a huge impact on my life, and shaped how I am as an adult.

It completely devastated me when I saw dozens of elderly asians being attacked in public for no reason! Those poor innocent people could have easily been my parents or grandparents. I think I’m more angry than shocked to be honest. Unfortunately, I had a horrible feeling that there would be a spike in anti-Asian hate crimes when COVID became a pandemic and not just an “Asia problem”.

The Asian community has long been boxed into this “model minority myth”. “If they can earn money and fit into society, why can’t the other foreigners?!” For the longest time, I’ve been taught to put my head down and work hard, and our community won’t be disturbed or targeted, which isn’t necessarily true. In a way, it has even made us compete with other minorities; if we are a “good” minority, there must a “bad” kind.

In 2020, during George Floyd’s murder, I remember posting my support on Instagram and then getting a response from one of my family members saying we shouldn’t say too much, and that it’s not our” battle” to fight. I think that’s the main problem, that we are taught not to complain, especially if it’s not our issue.

I think if there’s any positive thing we can get out of recent events, it’s that it has given Asians a platform to talk and express our thoughts and opinions. It has made me more vocal about my views – I no longer want to be that person that lets things slide because it doesn’t affect me. I don’t want to only be an ally, but also an activist who is brave enough to speak up, even if it’s not my race. I also want to be a parent who teaches their children not to be ashamed of their culture and background. I have hope for that.

Read more: We Chat To The Editor Of Spill Stories About “Black In Asia” Anthology

How Can I Support The Asian Community In Standing Against Anti-Asian Hate?

Anti-Asian hate won’t disappear overnight, but with your help, we can get one step closer to change. Whether you’re in Hong Kong or abroad, here are some ways you can support and stand with the Asian community:

Educate Yourself

Take the time to learn about the history of anti-Asian hate, as well as staying informed about what is currently happening today. Mainstream news sites rarely talk about Asian-specific instances of racism. Our top picks for news include NextShark and JackFroot. We also love Gold House for its celebration of Asian achievements, and Miscalcul[Asian] Magazine for its deep dives into the different Asian cultures and its history.

Speak Up

Living in Hong Kong, instances of outright anti-Asian hate are thankfully rare, yet micro-aggressions abound. Pull your friend up on that Asian joke they just cracked; challenge the casual sexualisation of Asian women instead of writing it off as drunken banter; educate loved ones abroad about why we shouldn’t be using the term “Wuhan flu”. It may seem small, but the social acceptance of this type of rhetoric contributes to a bigger picture which validates anti-Asian abuse more generally. Speak up, and make it clear that you won’t stand for it.

Donate

There are tons of great organisations doing work to support the Asian community, whether it’s by legally challenging racial discrimination, providing information to the wider public or offering practical resources to Asian victims. If you have money to spare, consider making a donation. Some good organisations to start with include Stop AAPI Hate, Stop ESEA Hate and Asian Mental Health Collective.

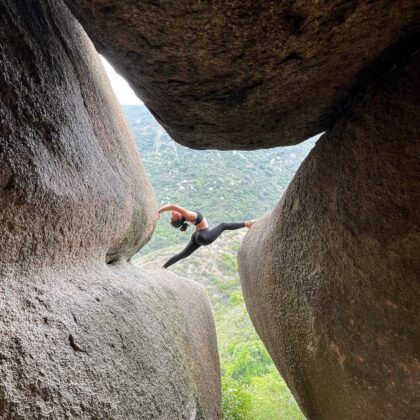

Images courtesy of Jason Leung via Unsplash and Tin Iglesias for Sassy Media Group.

Eat & Drink

Eat & Drink

Travel

Travel

Style

Style

Beauty

Beauty

Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness

Home & Decor

Home & Decor

Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Weddings

Weddings